A client shared this frustration with us recently:

“My mom finally agreed to go to the doctor, but then she didn’t tell her how she actually feels. What can I do?”

Unfortunately, it’s not uncommon for elderly adults either (1) to have difficulty communicating with their health care providers in general, or (2) to demonstrate an uncanny ability to tell the physician only the good news. Knowing which of these problems you’re having is important, so the first step is talking to your loved one about her experience at the doctor’s office.

Is she given the opportunity to talk about her concerns?

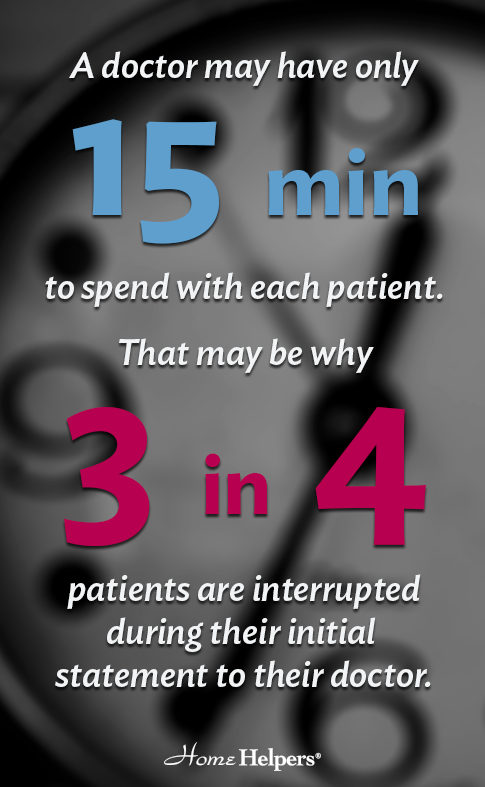

Like most other enterprises, health care practices are forced to add more and more efficiency to their operations. In an average day, the doctor may have only 15 minutes to spend with each appointment. That may be one reason a National Institutes of Health study found that fewer than one in four patients were able to complete their initial statement to their doctor before being interrupted.

Is she inadvertently hiding something from the doctor?

Your aging loved one is not so different from the rest of us. We all want to be seen as strong and healthy and not as complainers or in need of special accommodation. That’s how a real symptom like dizziness can become an everyday comment about needing to sit down once in a while. Or how consistent pain can be explained away as simple fatigue.

What you can do to improve your elderly loved one’s doctor visits:

Whatever the specific cause in your instance, take a moment to discuss it with your family member. Make it clear that you’re trying to gain an understanding and not accusing her of misleading her health care professional.

1. MAKE A LIST.

If some things are getting lost in translation, work together to create a written list of items to discuss at the doctor’s office. The simple presence of that list can make remembering topics easier and also lets the people in the office know that there are specific items to be discussed before the appointment ends.

2. WRITE A NOTE.

If you suspect Mom may be sugarcoating their actual symptoms in her conversation with the doctor, consider a call or a brief note to the doctor expressing your concerns. Keep in mind that privacy laws prevent health care professionals from discussing your loved one’s care without her permission, but it may make them aware of some specific questions to ask and things to talk to the actual patient about.

3. VISIT TOGETHER.

Finally, if your family member is willing, consider accompanying her to the doctor’s appointment. You can go just to take notes and help with any questions, so no one feels like you’re taking over the relationship. This is particularly important with the office staff. Some of our in-home elder care clients have reported that when a caregiver is present in the examination room—or even in the waiting room—the conversation can shift to one between the medical professional and the caregiver, to the exclusion of the patient herself. That doesn’t serve anyone’s interests.

Again, the key is openness. By making your family member comfortable discussing her care with you, you can help her to be her own advocate in protecting her health and independence.

Best,

Emma